Public schools in the United States were not always racially integrated. In 1954, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that segregating children in the public schools on the basis of race was inherently unequal and violated the United States Constitution. Fifteen years later, many public schools in Florida were still segregated.

Caroline Harvest and others filed a lawsuit in the Tampa Division of the Middle District of Florida against the Board of Public Instruction of Manatee County, Florida, alleging that the Manatee public schools were racially segregated and demanding that students not be assigned to specific schools on the basis of race.

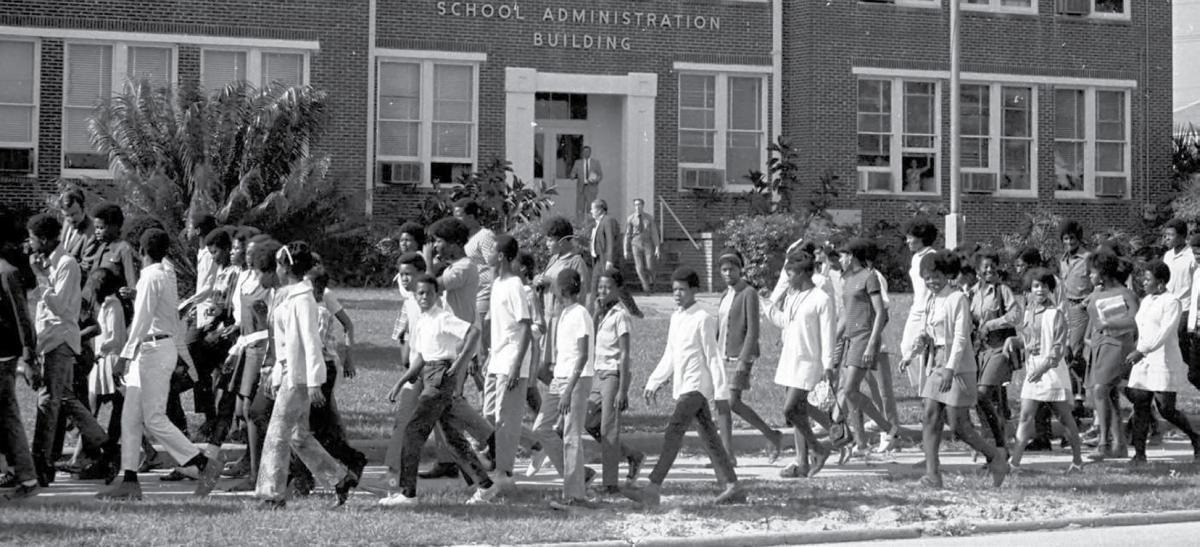

In January 1970, United States District Judge Ben Krentzman ordered that the Manatee County Schools must be desegregated by April 6, 1970. The day before the desegregation order was to take effect, Governor Kirk suspended the Superintendent and the Board of Public Instruction for the purpose of frustrating Judge Krentzman’s order. The next day, Judge Krentzman entered an order restraining Governor Kirk from any conduct that would impede the desegregation plan, as ordered by the court, and reinstated the superintendent and the school board.

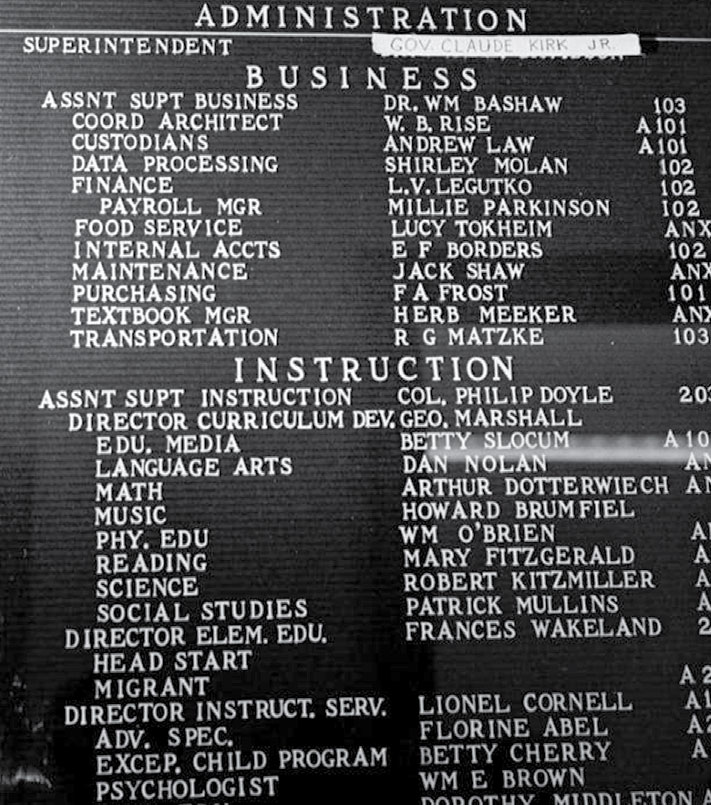

(left to right) Governor Claude Kirk, Jr., appoints himself school superintendent; protest march in front of the Manatee County school administration building; Governor Kirk at the school board

A Horrible, Illegal Act

Kirk declared Judge Krentzman’s Order to be “a horrible illegal act.” He dismissed the elected school board of Manatee County, installed himself as Manatee school superintendent and refused to comply with the court’s order.

The next day Judge Krentzman restrained Kirk from any actions impeding the desegregation and reinstated the board and the superintendent. Kirk again removed the school board demanding his "day in court”—but not just any court.

“I want to be in the supreme court on Friday or Saturday or Monday to get law on the subject of busing,” said Kirk.

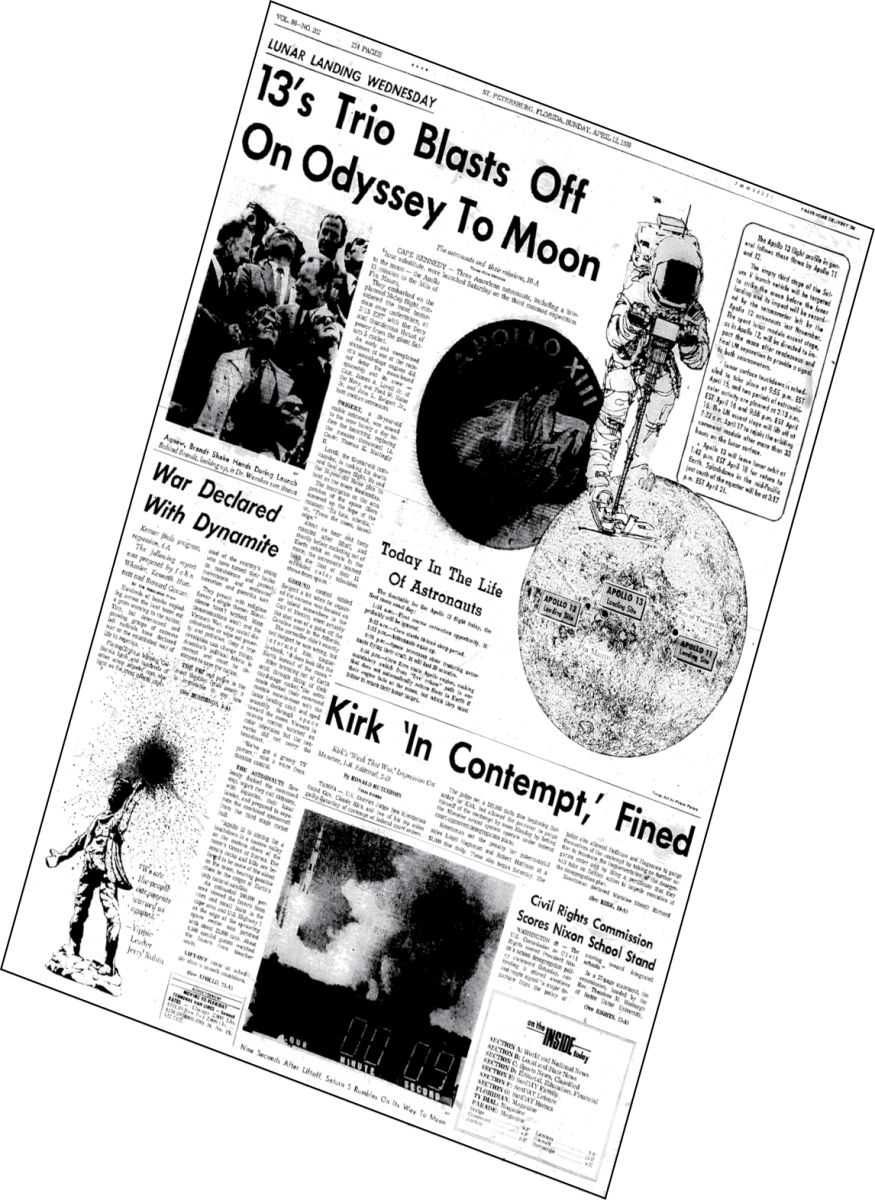

On April 11, 1970, Judge Krentzman held Governor Kirk in contempt of court after he failed to appear in court to answer to an order to show cause.

The judge ordered him to pay $10,000 per day, unless he ceased all interference with the court’s orders. Faced with the fine, Kirk immediately backed down, and the desegregation of the Manatee County public schools began.

This was the last time a southern governor ever tried to stand in the schoolhouse door and block a federal court order directing racial integration of schools.

(left to right) St. Petersburg Times | HEADLINE: Judge Orders Kirk Into Court;

HEADLINE: Claude Kirk's A Hero To Much Of Manatee; HEADLINE: Kirk 'In Contempt,' Fined

“The hearings made nationwide news and the courtroom was packed. Despite being ordered to, Kirk failed to show up. Judge Krentzman could have ordered United States Marshals to bring Kirk into court forcibly but chose not to. Kirk was very lucky in that respect.

“The hearings made nationwide news and the courtroom was packed. Despite being ordered to, Kirk failed to show up. Judge Krentzman could have ordered United States Marshals to bring Kirk into court forcibly but chose not to. Kirk was very lucky in that respect.

I was seated near the witness stand where I could hear and view everything that happened. Hagaman and Hoffman, Kirk‘s two administrative assistants, admitted following the governor’s orders to obstruct Judge Krentzman’s decision and announced that they would continue to do so if ordered by Kirk. Hagaman’s hands trembled. He was plainly terrified of what the judge might do to him, on account of his contempt of court.

The sheriff of Manatee County was a courtly, kindly, respectful man who confessed to the judge that he had followed Kirk’s orders but would henceforth follow the directives of the court, not Kirk. As a result, the sheriff was not fined by Judge Krentzman. The following day, a Saturday, a crowd of reporters eagerly awaited the court’s decisions on the matter of contempt. The United States Marshals obtained copies of the judgments, rented a private aircraft, and immediately flew up to Tallahassee to serve the papers on Kirk and his aides," said Donald E. Wilkes, Jr., law clerk to Judge Krentzman.

"I am sure that the judge received death threats. He had a deputy United States Marshal bodyguard for the next several weeks.” he said.

—Donald E. Wilkes, Jr., Law Clerk to Judge Krentzman